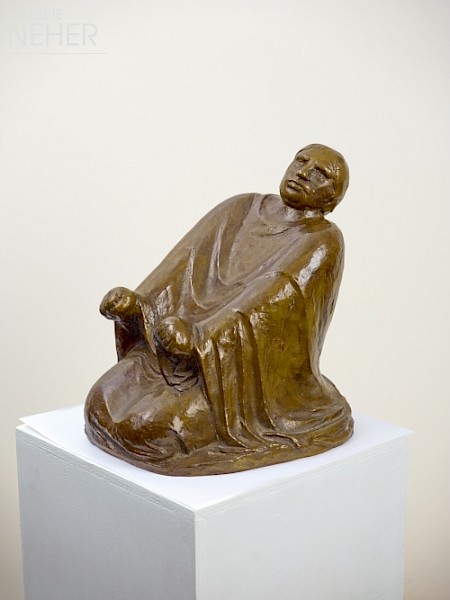

Ernst Barlach - Sitzender Gottvater (Seated God the Father), 1920

Bronze

48 x 42 x 30 cm

18 x 16 x 11 inch

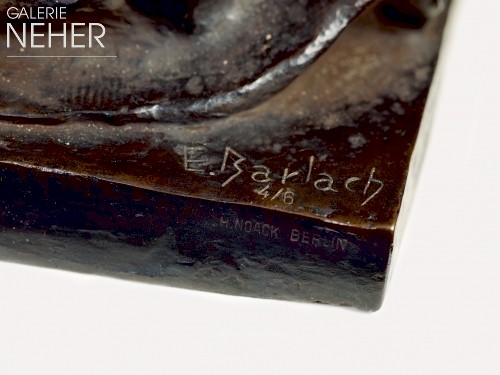

signed, numbered on the back left on the plinth: "E. Barlach 4/6"

including foundry mark: "H.NOACK BERLIN"

Edition: 6 numbered casts from 1983

Expertise;

Ernst Barlach Lizenzverwaltung, Ratzeburg

N 9441

Expertise:

Ernst Barlach Lizenensverwaltung, Ratzeburg

Provenance:

Estate of Ernst Barlach, Ratzeburg

Catalogue raisonné:

Elisabeth Laur, Ernst Barlach. Werkverzeichnis, Vol. 2, Das plastische Werk, Güstrow 2006,

no. 303

Exhibitions:

Essen, Galerie Neher, Herbst-Winter 2021, Katalog mit farbiger Abbildung Seite 19

Ernst Barlach - Sitzender Gottvater (Seated God the Father), 1920

Bronze

48 x 42 x 30 cm

18 x 16 x 11 inch

signed, numbered on the back left on the plinth: "E. Barlach 4/6"

including foundry mark: "H.NOACK BERLIN"

Edition: 6 numbered casts from 1983

Expertise;

Ernst Barlach Lizenzverwaltung, Ratzeburg

N 9441

Expertise:

Ernst Barlach Lizenensverwaltung, Ratzeburg

Provenance:

Estate of Ernst Barlach, Ratzeburg

Catalogue raisonné:

Elisabeth Laur, Ernst Barlach. Werkverzeichnis, Vol. 2, Das plastische Werk, Güstrow 2006,

no. 303

Exhibitions:

Essen, Galerie Neher, Herbst-Winter 2021, Katalog mit farbiger Abbildung Seite 19

About the work

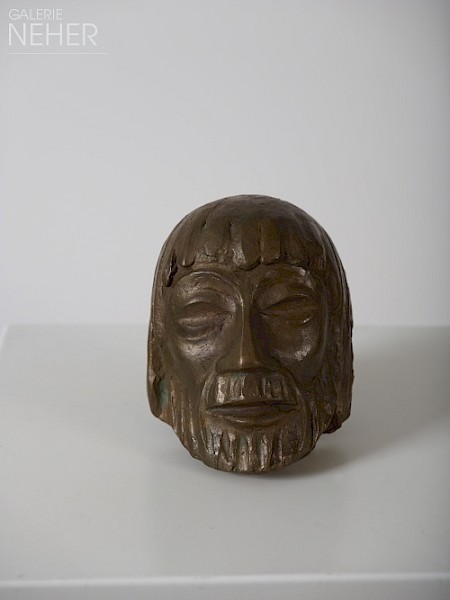

One finds many Christian-religious motifs in Ernst Barlach’s oeuvre. His Sitzender Gottvater (Seated God the Father) presents the creator of worlds more or less in passing and as deeply human. For Barlach, faith was a part of human reality. The artist grew up in a Protestant home, but it would be inappropriate to describe him as a Christian artist. Instead, the religious themes in his work can be understood as a search for the meaning of life. With his art, Barlach addresses the question of what distinguishes the human being, what moves him to create and persevere. “My pleasure and my urge to create repeatedly revolve around the problems of the meaning of life and other tall mountains in spiritual realms.”(1)

In one of his letters, he also wrote: “Dogma and church, profound faith in the teachings provide the artist with his motifs, but neither faith nor teachings are the essence, and are instead only aids and stimuli, providers of opportunity for the needs of the ‘rising above oneself’ of the creator.”(2)

The theme of his works is the human being per se, and all of the related questions about death, what comes after and resurrection. The consideration of whether there is a God, a higher power, is also an aspect of Barlach’s questions revolving around life. His creator of worlds is a benevolent, loving God. For purposes of comparison, reference can be made to the woodcut print from the picture sequence for Friedrich Schiller’s “Ode to Joy”, which, however, Barlach first worked on in 1924/25. One of the total of nine woodcut prints shows the figure of the creator of worlds in a gloriole, represented frontally in a long gown with tucked up legs and arms spread. Like in our bronze, God does not punish here, but instead blesses. He is a forgiving power. He approaches us with open arms to receive those who doubt and seek.

1 Cited from: Carl Dietrich, Ernst Barlach. Das plastische, graphische und dichterische Werk, Berlin 1958 , p. 117.

2 From the letter to Wolf-Dieter Zimmermann, dated 12.2.1933, cited from: Ernst Barlach, Die Briefe II. 1925–1938, ed. by Friedrich Droß, München 1969, p. 351, .

.

Text authored and provided by Dr Andrea Fink, art historian

The art historian, curator and freelance publicist Andrea Fink studied art history, cultural studies and humanities, modern history and philosophy in Bochum and Vienna. Doctorate in 2007 on the work of the Scottish artist Ian Hamilton Finlay. As a freelance curator and art consultant, her clients include, among others, the Kunstverein (art association) Ahlen, Kunstverein Soest, Wella Museum, Museum am Ostwall Dortmund, ThyssenKrupp AG, Kulturstiftung Ruhr, Osthaus Museum Hagen, Franz Haniel GmbH, Kunsthalle Krems, Austria.